The Language of Theseus

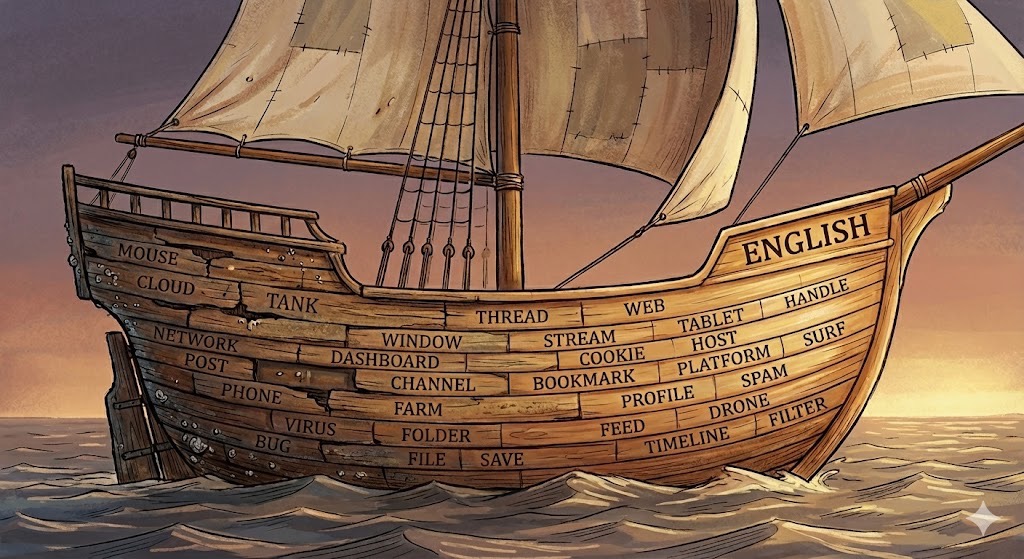

Imagine the Ship of Theseus. You replace one plank, then another, then another, until none of the original wood is left. Is it still the same ship?

Now swap planks for people.

Speakers are born into a language, use it for a few decades, and then vanish. New speakers arrive, inheriting the words and habits of those before them. The language community that speaks “English” in 2025 is not the same set of humans that spoke “English” in 1925, and yet we talk as if it’s one continuous thing.

Cognitive scientist Peter Gärdenfors puts it like this: even if meanings are determined by what’s in the heads of the users, those meanings can stay relatively constant as the users are gradually replaced. A word can seem to survive generations of turnover.

Call this idea the language of Theseus: the apparent continuity of a language even as its human planks are endlessly swapped out.

But words don’t just survive; they move.

When meanings quietly drift

We all know, at some level, that words change meaning over time. Historical linguists have catalogued thousands of these shifts, but you don’t need a PhD to feel it.

Take “mouse.”

For centuries, it’s a small furry animal you don’t want in your kitchen. In the late 20th century, it also becomes an input device you do want on your desk. Same sound, same spelling, new neighborhood of meaning.

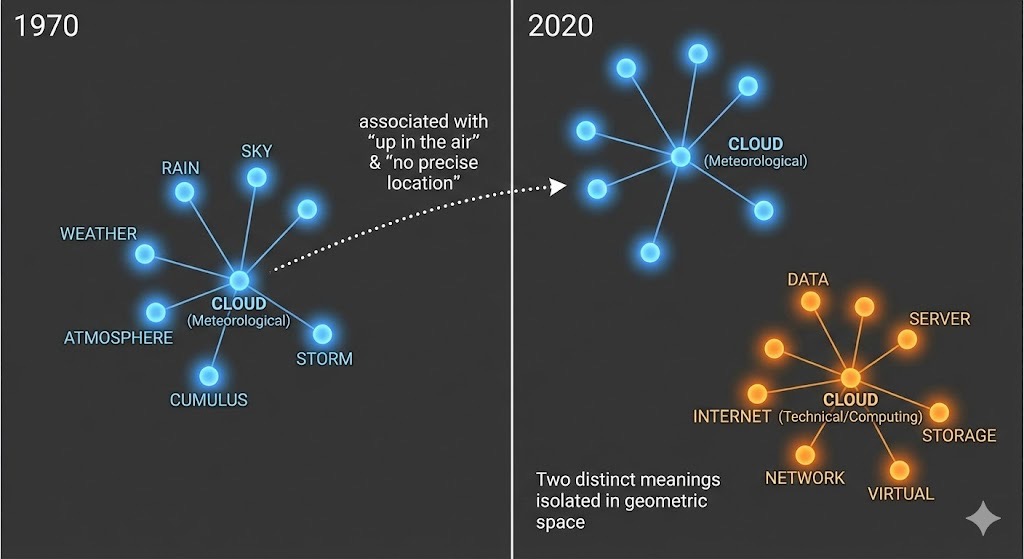

Or “cloud.”

Once: fluffy thing in the sky, neighbor to “rain” and “storm.” Now: also “the place your files go,” sitting near “data, server, platform” in tech talk.

Even “literally” has wandered. It used to insist “I’m not exaggerating.” Now you can say “I literally died laughing” without anyone calling an ambulance. The word’s job has shifted from precision to emphasis.

Our intuitions say: these words have drifted. But can we do more than nod and make a few before/after examples? Is there a way to see this drift in a more systematic, almost physical way?

Words as points in space

Enter word embeddings.

Modern language models often represent each word as a list of numbers – its coordinates in a high‑dimensional space. Each word becomes a point in this invisible cloud. Words used in similar contexts end up near each other. “Dog” is close to “cat” and “puppy,” far from “quantum” or “mortgage.”

You don’t have to love linear algebra to get the basic picture:

- The model learns a shape of language use.

- Distances in that shape reflect relationships in meaning.

Now add one simple twist: time.

Instead of training one model on all English text ever, you train separate models on different time slices: one on texts from 1900–1920, another from 1950–1970, another from 2000–2020. Each model gives you a snapshot of where words lived in meaning‑space during that period.

These are temporal embeddings – word embeddings indexed by time.

Line up those snapshots (there are standard mathematical tricks for aligning them), and you can literally watch a word’s position move across decades. Early on, the point for cloud hangs out next to “rain” and “storm.” Later, it begins to drift toward “server,” “storage,” “platform.” The word hasn’t just “changed meaning” in some vague way; its coordinates in this conceptual geometry have migrated.

The same goes for “mouse,” “literally,” and countless others. For some words, the path is smooth and gradual. For others, you get something like a fork: the word splits into two distinct senses that occupy different regions of the space.

From this perspective, the language of Theseus is no longer an abstract metaphor. It’s a movie: a point cloud wriggling and stretching as time goes by, words sliding into new neighborhoods while the overall structure of the language persists.

The shape of thought: a geometric Whorfian hypothesis

There’s a famous idea in linguistics associated with Benjamin Whorf: the languages we speak influence the way we think. If your language makes certain distinctions easy (like many words for snow) and others hard, it gently nudges what you notice, remember, and reason with.

Now overlay that idea on the embedding picture and you get a geometric twist:

- If meanings live as points in a geometric space,

- and that space has a certain shape – clusters, directions, gaps –

- then that shape influences which associations feel natural or immediate.

Call this the Geometric Whorfian Hypothesis: the geometry of our conceptual spaces helps structure our thought.

This is a working hypothesis, not a proven law of cognition. But it’s a useful lens. When a word like “cloud” moves into a new region of the space, neighboring “data” and “server,” it becomes easier to connect those concepts. When “literally” drifts away from careful, logical writing and toward hyperbolic storytelling, it becomes more natural to use it as an intensifier rather than a guarantee of accuracy.

Temporal embeddings don’t just document change; they suggest how the affordances for thought might be changing too. As the manifold – the overall shape of meaning – bends and warps, some mental paths shorten while others get longer.

Newspeak: hacking the manifold

George Orwell’s 1984 imagines a language engineered to control thought: Newspeak. The idea is simple and terrifying: if you remove or compress words for rebellious, critical, or nuanced ideas, it becomes harder to even formulate those thoughts.

“Bad” becomes “ungood.” “Excellent” becomes “plusgood.” More extreme criticism might be “doubleplusungood.” Subtle moral vocabulary is flattened into a few graded blobs.

In embedding terms, Newspeak is like taking a rich, detailed manifold and crushing it:

- Many distinct concepts that once occupied different regions of space are forced into almost the same coordinates.

- Entire directions in the space – along which people used to differentiate ideas like “injustice,” “resistance,” “freedom” – are deleted.

You still have a language of Theseus in the sense that new generations grow up speaking it, but the ship has been radically rebuilt. Its shape no longer lets you sail to certain conceptual destinations. The geometry has been edited to make some thoughts nearly inexpressible.

Orwell’s scenario is extreme and fictional, but it sharpens the point: if you can manipulate the geometry of meaning, you can influence what feels thinkable.

Seeing the Ship of Theseus

Return to Gärdenfors: meanings live in the heads of users, but can remain stable as those users are gradually replaced. With temporal embeddings, we can make that idea less mystical.

For some words, you’ll see remarkable stability. The point for “triangle” isn’t going anywhere; its neighbors stay like “angle,” “geometry,” “polygon.” The language of Theseus keeps that piece of the ship intact over long stretches.

For other words, you can trace long, slow drifts or dramatic jumps. The coordinates for “mouse” yank themselves toward “screen” and “click.” The manifold changes not just because individual speakers come and go, but because culture, technology, and power rearrange what goes with what.

The language of Theseus, in this geometric view, is a structure that both persists and flows. It persists enough that we can still read Shakespeare, if with footnotes. It flows enough that we routinely underestimate how different our ancestors’ meanings really were.

Temporal embeddings give us a way to watch the planks being swapped – to see the splits, the drifts, and the quiet revolutions in word meaning. And the Geometric Whorfian perspective invites a further question: as our shared meaning‑spaces keep bending, what kinds of thoughts are we making easier for future minds, and which ones are slowly drifting out of reach?

That’s the puzzle at the heart of the language of Theseus: not just whether it’s the same ship, but where, exactly, it’s sailing.